Home · Listener's Guide · The Songs · Who's Who · Liner Notes · Selected Tracks · What's New · Search

Phil Kraus

- Born 1918, New York City

- Died 13 January 2012, Houston, Texas

One of the hardest working men in Space Age Pop, Phil Kraus' motto might have been, "Have Percussion, Will Travel." Along with his frequent partner, Bobby Rosengarden, Kraus played on more percussion showcase albums than any other musician--except, perhaps, Dick Hyman, who had the advantage of never having to sleep.

One of the hardest working men in Space Age Pop, Phil Kraus' motto might have been, "Have Percussion, Will Travel." Along with his frequent partner, Bobby Rosengarden, Kraus played on more percussion showcase albums than any other musician--except, perhaps, Dick Hyman, who had the advantage of never having to sleep.

Kraus began studying the xylophone at the age of 8. His first music teacher suggested it after he resisted practicing the piano, and in Kraus' words, "I took to the xylophone right away." By the time he graduated from high school, was so proficient at most common percussion instruments that he won a full scholarship as a timpani major to the Juilliard School of Music.

Even then, he was working as a professional musician. During school breaks, he played in a combo with some friends: “We played at the Hotel Torrey in Harris, N.Y. There were four of us. The hotel promised to pay us $4 a week plus room and board and all the girls you wanted – if you could make them. We played at night after dinner from about 8 to 11 p.m. We always had a boy singer, a girl singer and a tap dancer."

He played with a few New York groups, including a very early all-electric combo with organist John Gart that played at the Hotel Shelton. His goal, however, was to follow in his older brother's footsteps and land a job in radio--“because it was a steady job.” In 1939, he joined the staff band of radio station WNEW. The core of the station band took the name, The Five Shades of Blue. "WNEW was a Class-B station, a local station not affiliated with a radio network. So, they only paid about $55 for a six-day week, compared with $100 a week at a Class-A station."

Kraus enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1941. Aside from Lionel Hampton, Kraus was one of the few professional vibraphonists at the time. Kraus was among the Army musicians selected to appear in Irving Berlin's patriotic musical, "This is the Army." The show opened at the Broadway Theater on July 4, 1942, where it played for three months, then did a national tour. “We played in the Broadway Theater for President Roosevelt, and we were invited to the White House, where we shook the president’s hand,” said Kraus. “The cast then made its way out to California, where we stayed there for several months making the movie version.”

After the war, he returned to New York and began a busy schedule of TV, radio, and recording session work that continued through the late 1970s. He played in studio bands for such TV shows as "Studio One," "Your Show of Shows," "The Perry Como Show," "The Ed Sullivan Show," and "The Jackie Gleason Show." He was a favorite of numerous arrangers and performers, and can be heard on recordings by Percy Faith, Hugo Winterhalter, Leroy Holmes, Andre Kostelanetz, Benny Goodman, and many others.

One of the few percussionists in New York skilled at a variety of instruments, Kraus was in constant demand for television, radio, advertising, Muzak, and recording sessions. He estimates that during his peak, he was working 7 days a week, covering as many as three sessions a day. He ventured out of New York City just once after the war, touring a few days with Frank Sinatra in the 1970s. Other than that, he enjoyed the luxury of more work than he had time to take, working constantly through three decades primarily on the basis of his reputation and acquaintances with music contractors like Carl Praeger.

He served as the anchorman of the percussion section for Bobby Shad's Time label through its "Series 2000" albums, which competed with Enoch Light's Command records, following the same format of bold black-and-white (and red, in Time's case) designs, gatefold covers, and dynamic stereo effects. At the same time, he also racked up his share of Command sessions on albums such as "Far Away Places."

He served as the anchorman of the percussion section for Bobby Shad's Time label through its "Series 2000" albums, which competed with Enoch Light's Command records, following the same format of bold black-and-white (and red, in Time's case) designs, gatefold covers, and dynamic stereo effects. At the same time, he also racked up his share of Command sessions on albums such as "Far Away Places."

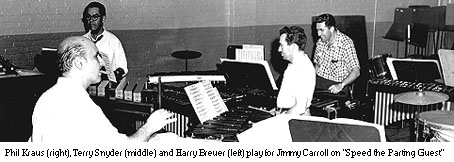

During this time, he teamed with Bobby Rosengarden for the first time on the Time album, "Like--Bongos." The pair formed a business partnership went on to record albums for RCA, Decca, and Project 3 during the 1960s. He worked with Dick Hyman as the Living Percussion on "The Beat Goes On," yet another in producer Ethel Gabriel's series of "Living (Blank)" albums for RCA's budget label, Camden. Hyman and Kraus each arranged 5 numbers for the album, which includes a fun cover of Les Baxter's "Quiet Village."

Kraus calculated that he performed on over 40 soundtracks, and thousands of Muzak sessions. Muzak recordings in particular were usually rush-through jobs, but Kraus recalled producer and arranger Sid Bass commenting, "They're on and off the elevator in a minute or two--who's going to notice a flub?" He worked with most of the other star session musicians of the New York scene: on Living Jazz and Brass Ring albums with Phil Bodner; on Al Caiola's guitar albums on United Artists; and with Tony Mottola on Command and Project 3 albums, as well as side jobs like a series of educational film strips on topics like magnetism and electricity.

His mark can be found in places throughout much of the popular music recorded in New York City between the late 1940s and late 1970s. On Ben E. King's classic, "Stand By Me," for example, that little scraping sound that appears between phrases ("When the night"

Kraus took his profession seriously and was active in the union movement and as a teacher. One of the early members of the Recording Musicians Association, he fought to win the right to residual payments for musicians who recorded on advertisement jingles, and he continues to encourage young musicians to join their local. He was sought out by many of his peers--including the great drummer Irv Cottler--to instruct them on fine points of techniques, and published five books. His three volumes on "Modern Mallet Method" are still in print and used as texts at the college level.

Kraus moved to Houston in 1978 to be closer to his children. He served as the personnel manager of the Houston Symphony for several years until he left to join the Houston Pops under Ned Bautista in 1981. He remained with the Pops until it folded in 1994. He continued to play vibes in small combos around the Houston area until just before his death. “My biggest regret? I have none," he told an interviewer in 2011. "I didn’t work too hard, had a nice time, nice friends, nice work."

S p a c e A g e P o p M u s i c

Recordings

with Bobby Rosengarden:

Home · Listener's Guide · The Songs · Who's Who · Liner Notes · Selected Tracks · What's New · Search

Email: editor@spaceagepop.com

© spaceagepop 2019. All rights reserved.